In physics, circular motion is a movement of an object along the circumference of a circle or rotation along a circular path. It can be uniform, with constant angular rate of rotation and constant speed, or non-uniform with a changing rate of rotation. The rotation around a fixed axis of a three-dimensional body involves circular motion of its parts. The equations of motion describe the movement of the center of mass of a body.

Examples of circular motion include: an artificial satellite orbiting the Earth at constant height, a stone which is tied to a rope and is being swung in circles, a car turning through a curve in a race track, an electron moving perpendicular to a uniform magnetic field, and a gear turning inside a mechanism.

Since the object's velocity vector is constantly changing direction, the moving object is undergoing acceleration by a centripetal forcein the direction of the center of rotation. Without this acceleration, the object would move in a straight line, according to Newton's laws of motion.

Uniform circular motion[edit]

In physics, uniform circular motion describes the motion of a body traversing a circular path at constant speed. The distance of the body from the axis of rotation remains constant at all times. Though the body's speed is constant, its velocity is not constant: velocity, a vector quantity, depends on both the body's speed and its direction of travel. This changing velocity indicates the presence of an acceleration; this centripetal acceleration is of constant magnitude and directed at all times towards the axis of rotation. This acceleration is, in turn, produced by a centripetal force which is also constant in magnitude and directed towards the axis of rotation.

In the case of rotation around a fixed axis of a rigid body that is not negligibly small compared to the radius of the path, each particle of the body describes a uniform circular motion with the same angular velocity, but with velocity and acceleration varying with the position with respect to the axis.

Formulas[edit]

For motion in a circle of radius r, the circumference of the circle is C = 2π r. If the period for one rotation is T, the angular rate of rotation, also known as angular velocity, ω is:

and the units are radians/sec

and the units are radians/sec

The speed of the object travelling the circle is:

The angle θ swept out in a time t is:

The angular acceleration,α of the particle is:

In the case of uniform circular motion α will be zero.

The acceleration due to change in the direction is:

The centripetal and centrifugal force can also be found out using acceleration:

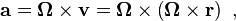

The vector relationships are shown in Figure 1. The axis of rotation is shown as a vector Ω perpendicular to the plane of the orbit and with a magnitude ω = dθ / dt. The direction of Ω is chosen using the right-hand rule. With this convention for depicting rotation, the velocity is given by a vector cross product as

which is a vector perpendicular to both Ω and r ( t ), tangential to the orbit, and of magnitude ω r. Likewise, the acceleration is given by

which is a vector perpendicular to both Ω and v ( t ) of magnitude ω |v| = ω2 r and directed exactly opposite to r ( t ).[1]

In the simplest case the speed, mass and radius are constant.

Consider a body of one kilogram, moving in a circle of radius one metre, with an angular velocity of one radian per second.

- The speed is one metre per second.

- The inward acceleration is one metre per square second[v^2/r]

- It is subject to a centripetal force of one kilogram metre per square second, which is one newton.

- The momentum of the body is one kg·m·s−1.

- The moment of inertia is one kg·m2.

- The angular momentum is one kg·m2·s−1.

- The kinetic energy is 1/2 joule.

- The circumference of the orbit is 2π (~ 6.283) metres.

- The period of the motion is 2π seconds per turn.

- The frequency is (2π)−1 hertz.

In polar coordinates[edit]

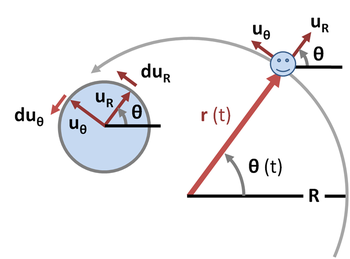

During circular motion the body moves on a curve that can be described in polar coordinate system as a fixed distance R from the center of the orbit taken as origin, oriented at an angle θ (t) from some reference direction. See Figure 4. The displacement vector  is the radial vector from the origin to the particle location:

is the radial vector from the origin to the particle location:

is the radial vector from the origin to the particle location:

is the radial vector from the origin to the particle location:

where  is the unit vector parallel to the radius vector at time t and pointing away from the origin. It is convenient to introduce the unit vector orthogonal to

is the unit vector parallel to the radius vector at time t and pointing away from the origin. It is convenient to introduce the unit vector orthogonal to  as well, namely

as well, namely  . It is customary to orient

. It is customary to orient  to point in the direction of travel along the orbit.

to point in the direction of travel along the orbit.

is the unit vector parallel to the radius vector at time t and pointing away from the origin. It is convenient to introduce the unit vector orthogonal to

is the unit vector parallel to the radius vector at time t and pointing away from the origin. It is convenient to introduce the unit vector orthogonal to  as well, namely

as well, namely  . It is customary to orient

. It is customary to orient  to point in the direction of travel along the orbit.

to point in the direction of travel along the orbit.

The velocity is the time derivative of the displacement:

Because the radius of the circle is constant, the radial component of the velocity is zero. The unit vector  has a time-invariant magnitude of unity, so as time varies its tip always lies on a circle of unit radius, with an angle θ the same as the angle of

has a time-invariant magnitude of unity, so as time varies its tip always lies on a circle of unit radius, with an angle θ the same as the angle of  . If the particle displacement rotates through an angle dθ in time dt, so does

. If the particle displacement rotates through an angle dθ in time dt, so does  , describing an arc on the unit circle of magnitude dθ. See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Hence:

, describing an arc on the unit circle of magnitude dθ. See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Hence:

has a time-invariant magnitude of unity, so as time varies its tip always lies on a circle of unit radius, with an angle θ the same as the angle of

has a time-invariant magnitude of unity, so as time varies its tip always lies on a circle of unit radius, with an angle θ the same as the angle of  . If the particle displacement rotates through an angle dθ in time dt, so does

. If the particle displacement rotates through an angle dθ in time dt, so does  , describing an arc on the unit circle of magnitude dθ. See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Hence:

, describing an arc on the unit circle of magnitude dθ. See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Hence:

where the direction of the change must be perpendicular to  (or, in other words, along

(or, in other words, along  ) because any change d

) because any change d in the direction of

in the direction of  would change the size of

would change the size of  . The sign is positive, because an increase in dθ implies the object and

. The sign is positive, because an increase in dθ implies the object and  have moved in the direction of

have moved in the direction of  . Hence the velocity becomes:

. Hence the velocity becomes:

(or, in other words, along

(or, in other words, along  ) because any change d

) because any change d in the direction of

in the direction of  would change the size of

would change the size of  . The sign is positive, because an increase in dθ implies the object and

. The sign is positive, because an increase in dθ implies the object and  have moved in the direction of

have moved in the direction of  . Hence the velocity becomes:

. Hence the velocity becomes:

The acceleration of the body can also be broken into radial and tangential components. The acceleration is the time derivative of the velocity:

The time derivative of  is found the same way as for

is found the same way as for  . Again,

. Again,  is a unit vector and its tip traces a unit circle with an angle that is π/2 + θ. Hence, an increase in angle dθ by

is a unit vector and its tip traces a unit circle with an angle that is π/2 + θ. Hence, an increase in angle dθ by  implies

implies  traces an arc of magnitude dθ, and as

traces an arc of magnitude dθ, and as  is orthogonal to

is orthogonal to  , we have:

, we have:

is found the same way as for

is found the same way as for  . Again,

. Again,  is a unit vector and its tip traces a unit circle with an angle that is π/2 + θ. Hence, an increase in angle dθ by

is a unit vector and its tip traces a unit circle with an angle that is π/2 + θ. Hence, an increase in angle dθ by  implies

implies  traces an arc of magnitude dθ, and as

traces an arc of magnitude dθ, and as  is orthogonal to

is orthogonal to  , we have:

, we have:

where a negative sign is necessary to keep  orthogonal to

orthogonal to  . (Otherwise, the angle between

. (Otherwise, the angle between  and

and  would decrease with increase in dθ.) See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Consequently the acceleration is:

would decrease with increase in dθ.) See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Consequently the acceleration is:

orthogonal to

orthogonal to  . (Otherwise, the angle between

. (Otherwise, the angle between  and

and  would decrease with increase in dθ.) See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Consequently the acceleration is:

would decrease with increase in dθ.) See the unit circle at the left of Figure 4. Consequently the acceleration is:

The centripetal acceleration is the radial component, which is directed radially inward:

while the tangential component changes the magnitude of the velocity:

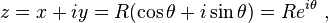

Using complex numbers[edit]

Circular motion can be described using complex numbers. Let the  axis be the real axis and the

axis be the real axis and the  axis be the imaginary axis. The position of the body can then be given as

axis be the imaginary axis. The position of the body can then be given as  , a complex "vector":

, a complex "vector":

axis be the real axis and the

axis be the real axis and the  axis be the imaginary axis. The position of the body can then be given as

axis be the imaginary axis. The position of the body can then be given as  , a complex "vector":

, a complex "vector":

where  is the imaginary unit, and

is the imaginary unit, and

is the imaginary unit, and

is the imaginary unit, and

is the angle of the complex vector with the real axis and is a function of time t. Since the radius is constant:

where a dot indicates time differentiation. With this notation the velocity becomes:

and the acceleration becomes:

The first term is opposite in direction to the displacement vector and the second is perpendicular to it, just like the earlier results shown before.

Discussion[edit]

Velocity[edit]

Figure 1 illustrates velocity and acceleration vectors for uniform motion at four different points in the orbit. Because the velocity v is tangent to the circular path, no two velocities point in the same direction. Although the object has a constant speed, its direction is always changing. This change in velocity is caused by an acceleration a, whose magnitude is (like that of the velocity) held constant, but whose direction also is always changing. The acceleration points radially inwards (centripetally) and is perpendicular to the velocity. This acceleration is known as centripetal acceleration.

For a path of radius r, when an angle θ is swept out, the distance travelled on the periphery of the orbit is s = rθ. Therefore, the speed of travel around the orbit is

,

,

where the angular rate of rotation is ω. (By rearrangement, ω = v/r.) Thus, v is a constant, and the velocity vector v also rotates with constant magnitude v, at the same angular rate ω.

Relativistic circular motion[edit]

In this case the three-acceleration vector is perpendicular to the three-velocity vector,

and the square of proper acceleration, expressed as a scalar invariant, the same in all reference frames,

becomes the expression for circular motion,

or, taking the positive square root and using the three-acceleration, we arrive at the proper acceleration for circular motion:

Acceleration[edit]

Main article: Acceleration

The left-hand circle in Figure 2 is the orbit showing the velocity vectors at two adjacent times. On the right, these two velocities are moved so their tails coincide. Because speed is constant, the velocity vectors on the right sweep out a circle as time advances. For a swept angle dθ = ω dt the change in v is a vector at right angles to v and of magnitude vdθ, which in turn means that the magnitude of the acceleration is given by

|v|

r

| 1 m/s 3.6 km/h 2.2 mph | 2 m/s 7.2 km/h 4.5 mph | 5 m/s 18 km/h 11 mph | 10 m/s 36 km/h 22 mph | 20 m/s 72 km/h 45 mph | 50 m/s 180 km/h 110 mph | 100 m/s 360 km/h 220 mph | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slow walk | Bicycle | City car | Aerobatics | |||||

| 10 cm 3.9 in | Laboratory centrifuge | 10 m/s² 1.0 g | 40 m/s² 4.1 g | 250 m/s² 25 g | 1.0 km/s² 100 g | 4.0 km/s² 410 g | 25 km/s² 2500 g | 100 km/s² 10000 g |

| 20 cm 7.9 in | 5.0 m/s² 0.51 g | 20 m/s² 2.0 g | 130 m/s² 13 g | 500 m/s² 51 g | 2.0 km/s² 200 g | 13 km/s² 1300 g | 50 km/s² 5100 g | |

| 50 cm 1.6 ft | 2.0 m/s² 0.20 g | 8.0 m/s² 0.82 g | 50 m/s² 5.1 g | 200 m/s² 20 g | 800 m/s² 82 g | 5.0 km/s² 510 g | 20 km/s² 2000 g | |

| 1 m 3.3 ft | Playground carousel | 1.0 m/s² 0.10 g | 4.0 m/s² 0.41 g | 25 m/s² 2.5 g | 100 m/s² 10 g | 400 m/s² 41 g | 2.5 km/s² 250 g | 10 km/s² 1000 g |

| 2 m 6.6 ft | 500 mm/s² 0.051 g | 2.0 m/s² 0.20 g | 13 m/s² 1.3 g | 50 m/s² 5.1 g | 200 m/s² 20 g | 1.3 km/s² 130 g | 5.0 km/s² 510 g | |

| 5 m 16 ft | 200 mm/s² 0.020 g | 800 mm/s² 0.082 g | 5.0 m/s² 0.51 g | 20 m/s² 2.0 g | 80 m/s² 8.2 g | 500 m/s² 51 g | 2.0 km/s² 200 g | |

| 10 m 33 ft | Roller-coaster vertical loop | 100 mm/s² 0.010 g | 400 mm/s² 0.041 g | 2.5 m/s² 0.25 g | 10 m/s² 1.0 g | 40 m/s² 4.1 g | 250 m/s² 25 g | 1.0 km/s² 100 g |

| 20 m 66 ft | 50 mm/s² 0.0051 g | 200 mm/s² 0.020 g | 1.3 m/s² 0.13 g | 5.0 m/s² 0.51 g | 20 m/s² 2 g | 130 m/s² 13 g | 500 m/s² 51 g | |

| 50 m 160 ft | 20 mm/s² 0.0020 g | 80 mm/s² 0.0082 g | 500 mm/s² 0.051 g | 2.0 m/s² 0.20 g | 8.0 m/s² 0.82 g | 50 m/s² 5.1 g | 200 m/s² 20 g | |

| 100 m 330 ft | Freeway on-ramp | 10 mm/s² 0.0010 g | 40 mm/s² 0.0041 g | 250 mm/s² 0.025 g | 1.0 m/s² 0.10 g | 4.0 m/s² 0.41 g | 25 m/s² 2.5 g | 100 m/s² 10 g |

| 200 m 660 ft | 5.0 mm/s² 0.00051 g | 20 mm/s² 0.0020 g | 130 m/s² 0.013 g | 500 mm/s² 0.051 g | 2.0 m/s² 0.20 g | 13 m/s² 1.3 g | 50 m/s² 5.1 g | |

| 500 m 1600 ft | 2.0 mm/s² 0.00020 g | 8.0 mm/s² 0.00082 g | 50 mm/s² 0.0051 g | 200 mm/s² 0.020 g | 800 mm/s² 0.082 g | 5.0 m/s² 0.51 g | 20 m/s² 2.0 g | |

| 1 km 3300 ft | High-speed railway | 1.0 mm/s² 0.00010 g | 4.0 mm/s² 0.00041 g | 25 mm/s² 0.0025 g | 100 mm/s² 0.010 g | 400 mm/s² 0.041 g | 2.5 m/s² 0.25 g | 10 m/s² 1.0 g |

Non-uniform[edit]

Non-uniform circular motion is any case in which an object moving in a circular path has a varying speed. The tangential acceleration is non-zero; the speed is changing.

Since there is a non-zero tangential acceleration, there are forces that act on an object in addition to its centripetal force(composed of the mass and radial acceleration). These forces include weight, normal force, and friction.

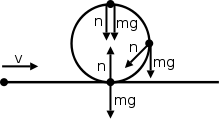

In non-uniform circular motion, normal force does not always point in the opposite direction of weight. Here is an example with an object traveling in a straight path then loops a loop back into a straight path again.

This diagram shows the normal force pointing in other directions rather than opposite to the weight force. The normal force is actually the sum of the radial and tangential forces that help to counteract the weight force and contribute to the centripetal force. The horizontal component of normal force is what contributes to the centripetal force. The vertical component of the normal force is what counteracts the weight of the object.

In non-uniform circular motion, normal force and weight may point in the same direction. Both forces can point down, yet the object will remain in a circular path without falling straight down. First let’s see why normal force can point down in the first place. In the first diagram, let's say the object is a person sitting inside a plane, the two forces point down only when it reaches the top of the circle. The reason for this is that the normal force is the sum of the weight and centripetal force. Since both weight and centripetal force points down at the top of the circle, normal force will point down as well. From a logical standpoint, a person who is traveling in the plane will be upside down at the top of the circle. At that moment, the person’s seat is actually pushing down on the person, which is the normal force.

The reason why the object does not fall down when subjected to only downward forces is a simple one. Think about what keeps an object up after it is thrown. Once an object is thrown into the air, there is only the downward force of earth’s gravity that acts on the object. That does not mean that once an object is thrown in the air, it will fall instantly. What keeps that object up in the air is its velocity. The first ofNewton's laws of motion states that an object’s inertia keeps it in motion, and since the object in the air has a velocity, it will tend to keep moving in that direction.

Applications[edit]

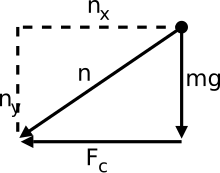

Solving applications dealing with non-uniform circular motion involves force analysis. With uniform circular motion, the only force acting upon an object traveling in a circle is the centripetal force. In non-uniform circular motion, there are additional forces acting on the object due to a non-zero tangential acceleration. Although there are additional forces acting upon the object, the sum of all the forces acting on the object will have to equal to the centripetal force.

Radial acceleration is used when calculating the total force. Tangential acceleration is not used in calculating total force because it is not responsible for keeping the object in a circular path. The only acceleration responsible for keeping an object moving in a circle is the radial acceleration. Since the sum of all forces is the centripetal force, drawing centripetal force into a free body diagram is not necessary and usually not recommended.

Using  , we can draw free body diagrams to list all the forces acting on an object then set it equal to

, we can draw free body diagrams to list all the forces acting on an object then set it equal to  . Afterwards, we can solve for what ever is unknown (this can be mass, velocity, radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, normal force, etc.). For example, the visual above showing an object at the top of a semicircle would be expressed as

. Afterwards, we can solve for what ever is unknown (this can be mass, velocity, radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, normal force, etc.). For example, the visual above showing an object at the top of a semicircle would be expressed as  .

.

, we can draw free body diagrams to list all the forces acting on an object then set it equal to

, we can draw free body diagrams to list all the forces acting on an object then set it equal to  . Afterwards, we can solve for what ever is unknown (this can be mass, velocity, radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, normal force, etc.). For example, the visual above showing an object at the top of a semicircle would be expressed as

. Afterwards, we can solve for what ever is unknown (this can be mass, velocity, radius of curvature, coefficient of friction, normal force, etc.). For example, the visual above showing an object at the top of a semicircle would be expressed as  .

.

In uniform circular motion, total acceleration of an object in a circular path is equal to the radial acceleration. Due to the presence of tangential acceleration in non uniform circular motion, that does not hold true any more. To find the total acceleration of an object in non uniform circular, find the vector sum of the tangential acceleration and the radial acceleration.

Radial acceleration is still equal to  . Tangential acceleration is simply the derivative of the velocity at any given point:

. Tangential acceleration is simply the derivative of the velocity at any given point:  . This root sum of squares of separate radial and tangential accelerations is only correct for circular motion; for general motion within a plane with polar coordinates

. This root sum of squares of separate radial and tangential accelerations is only correct for circular motion; for general motion within a plane with polar coordinates  , the Coriolis term

, the Coriolis term  should be added to

should be added to  , whereas radial acceleration then becomes

, whereas radial acceleration then becomes  .

.

. Tangential acceleration is simply the derivative of the velocity at any given point:

. Tangential acceleration is simply the derivative of the velocity at any given point:  . This root sum of squares of separate radial and tangential accelerations is only correct for circular motion; for general motion within a plane with polar coordinates

. This root sum of squares of separate radial and tangential accelerations is only correct for circular motion; for general motion within a plane with polar coordinates  , the Coriolis term

, the Coriolis term  should be added to

should be added to  , whereas radial acceleration then becomes

, whereas radial acceleration then becomes  .

.

and

and  in the unit vectors

in the unit vectors  and

and  for a small increment

for a small increment  in angle

in angle  .

.

No comments:

Post a Comment