| Thermodynamics |

|---|

The classical Carnot heat engine

|

| Book:Thermodynamics |

In thermodynamics, work performed by a system is the energy transferred by the system to another that is accounted for by changes in the external generalized mechanical constraints on the system. As such, thermodynamic work is a generalization of the concept of mechanical work in physics.

The external generalized mechanical constraints may be chemical,[1] electromagnetic,[1][2][3] (including radiative[4]), gravitational[5] or pressure/volume or other simply mechanical constraints,[6] including momental,[4] as in radiative transfer. Thermodynamic work is defined to be measurable solely from knowledge of such external macroscopic constraint variables. These macroscopic variables always occur in conjugate pairs, for example pressure and volume,[6] magnetic flux density and magnetization,[2] mole fraction and chemical potential.[1] In the SI system of measurement, work is measured in joules (symbol: J). The rate at which work is performed is power.

It is customary to calculate amount of energy transferred as work through quantities external to the system of interest, and thus belonging to its surroundings. Nevertheless, for historical reasons, the customary sign convention is to consider work done by the system on its surroundings as positive. Although all real physical processes entail some dissipation of kinetic energy, it is matter of principle that the dissipation that results from transfer of energy as work occurs only inside the system; energy dissipated outside the system, in the process of transfer of energy, is not counted as thermodynamic work. Thermodynamic work does not account for any energy transferred between systems as heat.

Mechanical thermodynamic work is performed by actions such as compression, and including shaft work, stirring, and rubbing. In the simplest case, for example, there are work of change of volume against a resisting pressure, and work without change of volume, known as isochoric work. An example of isochoric work is when an outside agency, in the surrounds of the system, drives a frictional action on the surface of the system. In this case the dissipation is not necessarily actually confined to the system, and the quantity of energy so transferred as work must be estimated through the overall change of state of the system as measured by both its mechanically and externally measurable deformation variables (such as its volume), and its non-deformation variable (usually internal to the system, for example its empirical temperature, regarded not as a temperature but simply as a mechanically measurable variable). In a process of transfer of energy by work, the internal energy of the final state of the system is then measured by the amount of adiabatic work of change of volume that would have been necessary to reach it from the initial state, such adiabatic work being measurable only through the externally measurable mechanical or deformation variables of the system, but including also full information about the forces exerted by the surroundings on the system during the process. In the case of some of Joule's measurements, the process was so arranged that heat produced outside the system by the frictional process was practically entirely transferred into the system during the process, so that the quantity of work done by the surrounds on the system could be calculated as shaft work, an external mechanical variable.[7][8] Forclosed systems, internal energy changes in a system other than as work transfer are as heat.

History[edit]

1824[edit]

Work, i.e. "weight lifted through a height", was originally defined in 1824 by Sadi Carnot in his famous paper Reflections on the Motive Power of Fire, he used the term motive power. Specifically, according to Carnot:

- We use here motive power to express the useful effect that a motor is capable of producing. This effect can always be likened to the elevation of a weight to a certain height. It has, as we know, as a measure, the product of the weight multiplied by the height to which it is raised.

1845[edit]

In 1845, the English physicist James Joule wrote a paper On the mechanical equivalent of heat for the British Association meeting inCambridge.[9] In this paper, he reported his best-known experiment, in which the mechanical power released through the action of a "weight falling through a height" was used to turn a paddle-wheel in an insulated barrel of water.

In this experiment, the friction and agitation of the paddle-wheel on the body of water caused heat to be generated which, in turn, increased the temperature of water. Both the temperature change ∆T of the water and the height of the fall ∆h of the weight mg were recorded. Using these values, Joule was able to determine the mechanical equivalent of heat. Joule estimated a mechanical equivalent of heat to be 819 ft•lbf/Btu (4.41 J/cal). The modern day definitions of heat, work, temperature, and energy all have connection to this experiment.

Overview[edit]

The first law of thermodynamics relates changes in the internal energy of a closed thermodynamic system to two forms of energy transfer, as heat and as work. Essential to the thermodynamic concept of work is that the energy transfer in fictive principle be able to occur at a finite rate without any of it necessarily being dissipated by friction or chemical degradation, which are necessarily dissipative. A thermodynamic dissipative process is one in which energy, internal, bulk flow kinetic, or system potential, is transduced from some initial form to some final form, the capacity to do mechanical work of the final form being less that that of the initial form. For example, transfer of energy as heat is dissipative because it is a transfer of internal energy from a body at one temperature to a body at a lower temperature. The second law of thermodynamics implies that this reduces the capacity of that internal energy to do mechanical work.

The concept of thermodynamic work is more general than that of simple mechanical work because it includes other types of energy transfers as well. Thermodynamic work is strictly and fully defined by its external generalized mechanical variables. The other form of energy transfer between closed systems is as heat. Heat is measured by change oftemperature of a known quantity of calorimetric material substance; it is of the essence of heat transfer that it is not mediated by the external generalized mechanical variables that define work. This distinction between work and heat is essential to thermodynamics.

Work refers to forms of energy transfer between closed systems that can be accounted for in terms of changes in the external macroscopic physical constraints on the system, for example energy which goes into expanding the volume of a system against an external pressure, by driving a piston-head out of a cylinder against an external force. The electrical work required to move a charge against an external electrical field can be measured.

This is in contrast to heat, which is primarily the energy that is transported or transduced as the microscopic thermal motions of particles and their associated inter-molecular potential energies,[10] or by thermal radiation.[11][12] There are two forms of macroscopic heat transfer by direct contact between a closed system and its surroundings:conduction,[13] and thermal radiation. There are several forms of dissipative transduction of energy that can occur internally within a system at a microscopic level, such as frictionincluding bulk and shear viscosity,[14] chemical reaction,[1] unconstrained expansion as in Joule expansion and in diffusion, and phase change;[1] these are not transfers of heat between systems. Convection of internal energy is a form a transport of energy but is in general not, as sometimes mistakenly supposed (a relic of the caloric theory of heat), a form of transfer of energy as heat, because convection is not in itself a microscopic motion of microscopic particles or their intermolecular potential energies, or photons; nor is it a of transfer of energy as work. Nevertheless, if the wall between the system and its surroundings is thick and contains fluid, in the presence of a gravitational field, convective circulation within the wall can be considered as indirectly mediating transfer of energy as heat between the system and its surroundings, though they are not in direct contact.

Formal definition[edit]

In thermodynamics, the quantity of work done by a closed system on its surroundings is defined by factors strictly confined to the interface of the surroundings with the system and to the surroundings of the system, for example an extended gravitational field in which the system sits, that is to say, to things external to the system. There are a few especially important kinds of thermodynamic work.

A simple example of one of those important kinds is pressure-volume work. The pressure of concern is that exerted by the surroundings on the surface of the system, and the volume of interest is the negative of the increment of volume gained by the system from the surroundings. It is usually arranged that the pressure exerted by the surroundings on the surface of the system is well defined and equal to the pressure exerted by the system on the surroundings. This arrangement for transfer of energy as work can be varied in a particular way that depends on the strictly mechanical nature of pressure-volume work. The variation consists in letting the coupling between the system and surroundings be through a rigid rod that links pistons of different areas for the system and surroundings. Then for a given amount of work transferred, the exchange of volumes involves different pressures, inversely with the piston areas, for mechanical equilibrium. This cannot be done for the transfer of energy as heat because of its non-mechanical nature.[15]

Another important kind of work is isochoric work, that is to say work that involves no eventual overall change of volume of the system between the initial and the final states of the process. Examples are friction on the surface of the system as in Rumford's experiment; shaft work such as in Joule's experiments; and slow vibrational action on the system that leaves its eventual volume unchanged, but involves friction within the system. Isochoric work for a body in its own state of internal thermodynamic equilibrium is done only by the surroundings on the body, not by the body on the surroundings, so that the sign of isochoric work with the present sign convention is always negative.

When work is done by a closed system that cannot pass heat in or out because it is adiabatically isolated, the work is referred to as being adiabatic in character. Adiabatic work can be of the pressure-volume kind or of the isochoric kind, or both.

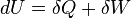

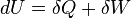

According to the first law of thermodynamics for a closed system, any net increase in the internal energy U must be fully accounted for, in terms of heat δQ entering the system and the work δW done by the system:[10]

The letter d indicates an exact differential, expressing that internal energy U is a property of the state of the system; they depend only on the original state and the final state, and not upon the path taken. In contrast, the Greek deltas (δ's) in this equation reflect the fact that the heat transfer and the work transfer are not properties of the final state of the system. Given only the initial state and the final state of the system, one can only say what the total change in internal energy was, not how much of the energy went out as heat, and how much as work. This can be summarized by saying that heat and work are not state functions of the system.[10]

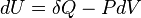

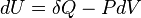

The minus sign in front of  indicates that a positive amount of work done by the system leads to energy being lost from the system. This is the sign convention for work in many textbooks on physics. This sign convention entails that a non-zero quantity of isochoric work always has a negative sign, because of the second law of thermodynamics.

indicates that a positive amount of work done by the system leads to energy being lost from the system. This is the sign convention for work in many textbooks on physics. This sign convention entails that a non-zero quantity of isochoric work always has a negative sign, because of the second law of thermodynamics.

indicates that a positive amount of work done by the system leads to energy being lost from the system. This is the sign convention for work in many textbooks on physics. This sign convention entails that a non-zero quantity of isochoric work always has a negative sign, because of the second law of thermodynamics.

indicates that a positive amount of work done by the system leads to energy being lost from the system. This is the sign convention for work in many textbooks on physics. This sign convention entails that a non-zero quantity of isochoric work always has a negative sign, because of the second law of thermodynamics.

(An alternate sign convention is to consider the work performed on the system by its surroundings as positive. This leads to a change in sign of the work, so that  . This is the convention adopted by many modern textbooks of physical chemistry.)

. This is the convention adopted by many modern textbooks of physical chemistry.)

. This is the convention adopted by many modern textbooks of physical chemistry.)

. This is the convention adopted by many modern textbooks of physical chemistry.)Pressure-volume work[edit]

Pressure-volume work (or PV work) occurs when the volume V of a system changes. PV work is often measured in units of litre-atmospheres where 1L·atm = 101.325J. However, the litre-atmosphere is not a recognised unit in the SI system of units, which measures P in Pascal (Pa), V in m3, and PV in Joule (J), where 1 J = 1 Pa.m3. PV work is an important topic in chemical thermodynamics.

For a reversible process in a closed system, PV work is represented by the following differential equation:

where

denotes an infinitesimal increment of work done by the system;

denotes an infinitesimal increment of work done by the system; denotes the pressure inside the system and outside the system, against which the system expands; the two pressures are practically equal for a reversible process;

denotes the pressure inside the system and outside the system, against which the system expands; the two pressures are practically equal for a reversible process; denotes the infinitesimal increment of the volume of the system.

denotes the infinitesimal increment of the volume of the system.

Moreover,

where

denotes the work done by the system during the whole of the reversible process.

denotes the work done by the system during the whole of the reversible process.

The first law of thermodynamics can then be expressed as

(In the alternate sign convention where W = work done on the system,  . However,

. However,  is unchanged.)

is unchanged.)

. However,

. However,  is unchanged.)

is unchanged.)Path dependence[edit]

As for all kinds of work, in general PV work is path-dependent and is therefore a thermodynamic process function. The statement that a process is reversible and adiabatic serves as a specification of the path, but does not determine the path uniquely, because the path can include several slow goings backward and forward in volume, as long as there is no transfer of energy as heat. The first law of thermodynamics states  . For an adiabatic process,

. For an adiabatic process,  and thus the integral amount work done is equal to the change in internal energy. For a reversible adiabatic process, the integral amount of work done during the process depends only on the initial and final states of the process, and is the one and the same for every intermediate path.

and thus the integral amount work done is equal to the change in internal energy. For a reversible adiabatic process, the integral amount of work done during the process depends only on the initial and final states of the process, and is the one and the same for every intermediate path.

. For an adiabatic process,

. For an adiabatic process,  and thus the integral amount work done is equal to the change in internal energy. For a reversible adiabatic process, the integral amount of work done during the process depends only on the initial and final states of the process, and is the one and the same for every intermediate path.

and thus the integral amount work done is equal to the change in internal energy. For a reversible adiabatic process, the integral amount of work done during the process depends only on the initial and final states of the process, and is the one and the same for every intermediate path.

If the process took a path other than an adiabatic path, the work would be different. This would only be possible if heat flowed into/out of the system. In a non-adiabatic process, there are indefinitely many paths between the initial and final states.

In another notation, δW is written đW (with a line through the d). This notation indicates that đW is not an exact one-form. The line-through is merely a flag to warn us there is actually no function (0-form) W which is the potential of đW. If there were, indeed, this function W, we should be able to just use Stokes Theorem to evaluate this putative function, the potential of đW, at the boundary of the path, that is, the initial and final points, and therefore the work would be a state function. This impossibility is consistent with the fact that it does not make sense to refer to the work on a point in the PV diagram; work presupposes a path.

Other mechanical forms of work[edit]

There are several ways of doing work, each in some way related to a force acting through a distance.[17] In basic mechanics,the work done by a constant force F on a body displaced a distance s in the direction of the force is given by

If the force is not constant, the work done is obtained by integrating the differential amount of work,

Shaft work[edit]

Energy transmission with a rotating shaft is very common in engineering practice. Often the torque T applied to the shaft is constant which means that the force F applied is constant. For a specified constant torque, the work done during n revolutions is determined as follows: A force F acting through a moment arm r generates a torque T

→

→

This force acts through a distance s, which is related to the radius r by

The shaft work is then determined from:

The power transmitted through the shaft is the shaft work done per unit time, which is expressed as

Spring work[edit]

When a force is applied on a spring, and the length of the spring changes by a differential amount dx, the work done is

For linear elastic springs, the displacement x is proportional to the force applied

,

,

where K is the spring constant and has the unit of N/m. The displacement x is measured from the undisturbed position of the spring (that is, X=0 when F=0). Substituting the two equations

,

,

where x1 and x2 are the initial and the final displacement of the spring respectively, measured from the undisturbed position of the spring.

Work done on elastic solid bars[edit]

Solids are often modeled as linear springs because under the action of a force they contract or elongate, and when the force is lifted, they return to their original lengths, like a spring. This is true as long as the force is in the elastic range, that is, not large enough to cause permanent or plastic deformation. Therefore, the equations given for a linear spring can also be used for elastic solid bars. Alternately, we can determine the work associated with the expansion or contraction of an elastic solid bar by replacing the pressure P by its counterpart in solids, normal stress σ=F/A in the work expansion

where A is the cross sectional area of the bar.

Work associated with the stretching of liquid film[edit]

Consider a liquid film such as a soap film suspended on a wire frame. Some force is required to stretch this film by the movable portion of the wire frame. This force is used to overcome the microscopic forces between molecules at the liquid-air interface. These microscopic forces are perpendicular to any line in the surface and the force generated by these forces per unit length is called the surface tension σ whose unit is N/m. Therefore the work associated with the stretching of a film is called surface tension work, and is determined from

where dA=2b dx is the change in the surface area of the film. The factor 2 is due to the fact that the film has two surfaces in contact with air. The force acting on the moveable wire as a result of surface tension effects is F=2b σ, where σ is the surface tension force per unit length.

Free energy and exergy[edit]

The amount of useful work which may be extracted from a thermodynamic system is determined by the second law of thermodynamics. Under many practical situations this can be represented by the thermodynamic availability, or Exergy, function. Two important cases are: in thermodynamic systems where the temperature and volume are held constant, the measure of useful work attainable is the Helmholtz free energy function; and in systems where the temperature and pressure are held constant, the measure of useful work attainable is the Gibbs free energy.

Non-mechanical forms of work[edit]

Non-mechanical work in thermodynamics is work determined by long-range forces penetrating into the system as force fields. The action of such forces can be initiated by events in the surroundings of the system, or by thermodynamic operations on the shielding walls of the system. The long-range forces are forces in the ordinary physical sense of the word, not the so-called 'thermodynamic forces' of non-equilibrium thermodynamic terminology.

The non-mechanical work of long-range forces can have either positive or negative sign, work being done by the system on the surroundings, or vice versa. Work done by long-range forces can be done indefinitely slowly, so as to approach the fictive reversible quasi-static ideal, in which entropy is not created in the system by the process.

In thermodynamics, non-mechanical work is to be contrasted with mechanical work that is done by forces in immediate contact between the system and its surroundings. If the putative 'work' of a process cannot be defined as either long-range work or else as contact work, then sometimes it cannot be described by the thermodynamic formalism as work at all. Nevertheless, the thermodynamic formalism allows that energy can be transferred between an open system and its surroundings by processes for which work is not defined. An example is when the wall between the system and its surrounds is not considered as idealized and vanishingly thin, so that processes can occur within the wall, such as friction affecting the transfer of matter across the wall; in this case, the forces of transfer are neither strictly long-range nor strictly due to contact between the system and its surrounds; the transfer of energy can then be considered as by convection, and assessed in sum just as transfer of internal energy. This is conceptually different from transfer of energy as heat through a thick fluid-filled wall in the presence of a gravitational field, between a closed system and its surroundings; in this case there may convective circulation within the wall but the process may still be considered as transfer of energy as heat between the system and its surroundings; if the whole wall is moved by the application of force from the surroundings, without change of volume of the wall, so as to change the volume of the system, then it is also at the same time transferring energy as work. A chemical reaction within a system can lead to electrical long-range forces and to electric current flow, which transfer energy as work between system and surroundings, though the system's chemical reactions themselves (except for the special limiting case in which in they are driven through devices in the surroundings so as to occur along a line of thermodynamic equilibrium) are always irreversible and do not directly interact with the surroundings of the system.[18]

Non-mechanical work contrasts with pressure-volume work. Pressure-volume work is one of the two mainly considered kinds of mechanical contact work. A force acts on the interfacing wall between system and surroundings. The force is that due to the pressure exerted on the interfacing wall by the material inside the system; that pressure is an internal state variable of the system, but is properly measured by external devices at the wall. The work is due to change of system volume by expansion or contraction of the system. If the system expands, in the present article it is said to do positive work on the surroundings. If the system contracts, in the present article it is said to do negative work on the surroundings. Pressure-volume work is a kind of contact work, because it occurs through direct material contact with the surrounding wall or matter at the boundary of the system. It is accurately described by changes in state variables of the system, such as the time courses of changes in the pressure and volume of the system. The volume of the system is classified as a "deformation variable", and is properly measured externally to the system, in the surroundings. Pressure-volume work can have either positive or negative sign. Pressure-volume work, performed slowly enough, can be made to approach the fictive reversible quasi-static ideal.

Non-mechanical work also contrasts with shaft work. Shaft work is the other of the two mainly considered kinds of mechanical contact work. It transfers energy by rotation, but it does not eventually change the shape or volume of the system. Because it does not change the volume of the system it is not measured as pressure-volume work, and it is called isochoric work. Considered solely in terms of the eventual difference between initial and final shapes and volumes of the system, shaft work does not make a change. During the process of shaft work, for example the rotation of a paddle, the shape of the system changes cyclically, but this does not make an eventual change in the shape or volume of the system. Shaft work is a kind of contact work, because it occurs through direct material contact with the surrounding matter at the boundary of the system. A system that is initially in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium cannot initiate any change in its internal energy. In particular, it cannot initiate shaft work. This explains the curious use of the phrase"inanimate material agency" by Kelvin in one of his statements of the second law of thermodynamics. Thermodynamic operations or changes in the surroundings are considered to be able to create elaborate changes such as indefinitely prolonged, varied, or ceased rotation of a driving shaft, while a system that starts in a state of thermodynamic equilibrium is inanimate and cannot spontaneously do that.[19] Thus the sign of shaft work is always negative, work being done on the system by the surroundings. Shaft work can hardly be done indefinitely slowly; consequently it always produces entropy within the system, because it relies on friction or viscosity within the system for its transfer.[20] The foregoing comments about shaft work apply only when one ignores that the system can store angular momentum and its related energy.

Examples of non-mechanical work modes include

- Electrical work – where the force is defined by the surroundings' voltage (the electrical potential) and the generalized displacement is change of spatial distribution of electrical charge

- Magnetic work – where the force is defined by the surroundings' magnetic field strength and the generalized displacement is change of total magnetic dipole moment

- Electrical polarization work – where the force is defined by the surroundings' electric field strength and the generalized displacement is change of the polarization of the medium (the sum of the electric dipole moments of the molecules)

- Gravitational work – where the force is defined by the surroundings' gravitational field and the generalized displacement is change of the spatial distribution of the matter within the system.

No comments:

Post a Comment